Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Asthma Control and Exacerbations Among Adult Asthmatics

Md Shamim Akhtar1*, Varsha AM1, Madhu Kanodia2 and Neethu Thomas3

1Head Department of Respiratory Medicine, St Stephen’s Hospital, Delhi

2DNB Resident Department of Respiratory Medicine, St Stephen’s Hospital, Delhi

3Senior Specialist Department of Respiratory Medicine, St Stephen’s Hospital, Delhi

Submission: November 27, 2025; Published: December 15, 2025

*Corresponding author: Dr Md Shamim Akhtar, Head Department of Respiratory Medicine, St. Stephen’s Hospital, Delhi

How to cite this article: Md Shamim A, Varsha AM, Madhu K, Neethu T. Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Asthma Control and Exacerbations Among Adult Asthmatics. Int J Pul & Res Sci. 2025; 8(2): 555734.DOI: 10.19080/IJOPRS.2025.08.555734

Abstract

Background: Tobacco smoking is associated with more severe asthma symptoms, an accelerated decline in lung function, increased number of exacerbation, and reduced responses to inhaled corticosteroids. The asthmatic smoker may represent a distinct phenotype with definite immune cellular changes, as well as impaired pharmacological effects and poor responses to asthma management. Our objective was to compare asthma outcomes in terms of disease control, exacerbation rates, and lung function in a population of asthmatic patients according to their smoking status. and to study the factors influencing asthma control in these patients.

Methods: We compared patients’ demographics, disease characteristics, mMRC dyspnoea score, lung-function parameters, asthma control questionnaire (ACQ 5) score and exacerbation rates in current-smokers (CS, n = 40), former-smokers (FS, n = 16), and never-smokers (NS, n = 94), and identified factors predicting poor asthma control.

Results: Current smokers had more symptoms with higher mean dyspnoea score, poor lung function, an increased number of exacerbations, poor response to treatment and higher rate of uncontrolled asthma as compared to former smokers and non-smokers. The mean asthma control questionnaire’s (ACQ) score was higher in CS vs. FS and NS (1.84 vs. 1.02 vs 0.56, p <0.001). Compared to CS, FS and non-smokers had a lower rate of exacerbations, a better ACQ score (similar to NS), less severe dyspnoea, and better lung function parameters.

Conclusion: Cigarette smoking is associated with worse asthma outcomes for a range of clinical and functional respiratory variables compared to non-smokers and former smokers, thus supporting the importance of smoking cessation in this population

Keywords:Tobacco smoking; Asthma control; Exacerbation’s; Lung function; Smoking cessation

Abbreviations:ICS: Inhaled Corticosteroids; CS: Current Smokers; FS: Former Smokers; NS: Never Smokers; GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1; BMI: Body Mass Index; ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation and variable airflow limitation that produces symptoms such as dyspnoea, wheezing, cough, and chest tightness which vary over time and in intensity. The prevalence of asthma is estimated at up to 18% in the general population [1]. There are several reasons for the increased occurrence of bronchial asthma in developing countries like India, including changes in lifestyle, industrialization, air pollution and urbanization [2]. The goals of asthma management are to achieve good symptom control, and to reduce the risk of exacerbation, persistent airflow limitation and asthma related mortality with minimal side effects of the treatment. One of the major risk factors that alter the progression of the disease, and the treatment outcome is tobacco smoking. Despite their chronic respiratory symptoms, about 20% of asthmatics commence and continue with smoking, with a prevalence rate that is close to what is found in the general population [3].

The basic pathophysiology in asthma is an immune overreaction to otherwise innocuous antigens, that results in the release of TH2 cytokines, interleukins 4, 5 and 13. IL-4 and IL-13 promotes specific IgE production against the antigens encountered and IL-5 helps in eosinophil maturation and survival [4]. Patients with asthma who continue to smoke have more severe symptoms, worse health related quality of life with a huge impact on healthcare resources due to unscheduled doctor visits and frequent hospital admissions. Cigarette smoking in asthma is associated with higher frequency of exacerbations as well as they are less sensitive to the beneficial effects of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) which are the mainstay of controller treatments for asthma [5]. Thus, tobacco smoking and asthma can be a dangerous mix, posing multiple challenges to the clinician and the patient. This entails that greater efforts need to be employed to develop safe and effective smoking cessation programme and avoidance strategies to improve clinical outcomes [6]. The asthmatic smoker may represent a distinct phenotype with immune cellular changes, as well as impaired pharmacological effects and poor responses to asthma management.

However, there are only limited published data, establishing the association between asthma and tobacco smoking. The need for smoking cessation is often emphasized in asthma-management guidelines, but recent data about the effects of active smoking and smoking cessation on asthma outcomes are lacking. In the present study, we aim to assess the influence of active tobacco smoking on asthma control, exacerbation rate, and lung-function parameters among three groups of asthmatic patients with different smoking histories (never-smokers, former-smokers, and current-smokers) as well as to identify the factors associated with asthma control in this population.

Methodology

Study design: Three-group observational study with repeated measures at baseline, 3 months, and 1 year.

Study groups: Current Smokers (CS), Former Smokers (FS), Never Smokers (NS). A prospective, observational study was conducted in 150 adult asthmatics attending the outpatient clinic at the department of Respiratory medicine, St Stephen’s Hospital Delhi between June 2022 - March 2024. The diagnosis of asthma was established by a respiratory physician according to Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines [1]. All patients had asthma symptoms and either an airflow reversibility (increase in forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) > 12% reported to baseline and 200ml following inhalation of 400μg salbutamol. The whole set of patients were categorized into three groups based on their smoking histories as never smokers (NS), former smokers (FS), and current smokers (CS) and were recruited into the study after getting written and signed informed consents. They were initiated on treatment as per the 2021 GINA guidelines and were followed up regularly at three months and one year of the study. Patients with cardiovascular diseases (such as angina, myocardial infarction, congestive failure, rheumatic heart disease), active malignancy, active pulmonary tuberculosis, COPD and those on immunosuppressive therapy were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee [SSHEC_R0356].

Patients were subjected to detailed history taking and general as well as systemic examination, and data was collected regarding their age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking status and tobacco exposure (estimated as number of pack-years), presence of dyspnoea (quantified according to mMRC grading), asthma symptom control by ACQ5 scoring, lung function parameters, number of exacerbations in a year. Based on their smoking pattern the patients were categorized into 3 groups for comparison- (a) Current smokers - An adult who has smoked 100 cigarettes in his/ her lifetime and who currently smokes cigarettes (b) Former smoker - An adult who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his/ her lifetime, but who had quit smoking at the time of the study and © never smoker - An adult who has never smoked or who has smoked less than 100 cigarettes in his/ her lifetime. Dyspnoea was evaluated according to the modified medical council research [mMRC] score, a self-rating tool to measure the degree of disability that breathlessness poses on day-to-day activities: 0—no breathlessness except on strenuous exercise; 1—shortness of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill; 2—walks slower than people of same age on the level because of breathlessness or has to stop to catch breath when walking at their own pace on the level; 3—stops for breath after walking ∼100m or after few minutes on the level; and 4—too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing.

Asthma control was assessed with the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ 5) as controlled or partially controlled asthma was defined as an ACQ score ≤ 1.5, and uncontrolled asthma was defined as a score > 1.5. Asthma exacerbation was defined as a worsening of respiratory symptoms for more than 24h and requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids for at least three days, and was assessed for the previous year before inclusion in the study. Pulmonary function tests (Done using PFT machine from Care Fusion) - To assess the lung function (FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, PEFR) & using flow volume curves. Sputum for AFB staining with 2 samples to rule out pulmonary tuberculosis whenever indicated. Chest X ray to rule out active tuberculosis or malignancy.

Outcomes: Lung function parameters including FVC (% predicted), FEV1 (% predicted), FEV1/FVC (%), Asthma control questionnaire ACQ-5, and number of exacerbations in the last year.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 by IBM USA. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages (%) and continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and median. Because normality is uncertain and the FS group is relatively small (n=16), non-parametric tests were used by default. Between-group differences at each time point: Kruskal-Wallis test, with pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests and Holm adjustment. Within-group change over time (Baseline → 3 months → 1 year) using Friedman test and exacerbations by Kruskal-Wallis with pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests. A p value of < 0.05 was be considered statistically significant.

Results

The three study groups (NS, FS, and CS) were comparable in terms of age, body mass index (BMI), family history asthma (more than 35% of patients in each group), age of asthma onset (more than half of patients in each group had late-onset asthma). Mean age of the patient among current smoker was 39±5.6 years, former smoker was 36±4.8 years and non-smokers was 34±4.2 years which was non statistically significant. Among former smokers, 81.2% were men and 18.8% were women. Women made up around 62.8% of those who had never smoked and 37.2% of never smokers were men. 40% of current smokers, 37.5% of former smokers, and 50% of never smokers had a family history of asthma.

Majority of smokers - former and current - fell within the 18.5 to 25.0kg/m2 BMI range. 7.5% of the current smokers, 6.2% of former smokers and 23.4% of never smokers were obese. About 25.0% of current smokers, 25.0% of past smokers, and 5.3% of never smokers had grade 3 dyspnoea at baseline. The distinction between the degree of dyspnoea and smoking status was statistically significant (Table 1). The findings of this study demonstrate a strong and consistent association between tobacco smoking and adverse asthma outcomes. Across 150 patients, comprising 40 current smokers (CS), 16 former smokers (FS), and 94 never smokers (NS), current smokers showed the poorest results in terms of lung function, asthma control, and exacerbation rates. Former smokers occupied an intermediate position, indicating that cessation confers measurable benefits, though not to the level of never smokers.

Lung Function

At baseline, mean FVC values were already lower in CS (59.8 ± 8.7%) compared to FS (58.9 ± 8.2%) and NS (65.9 ± 4.99%), with between-group differences significant (Kruskal-Wallis H=23.61, p<0.001). This gap widened by one year, when NS maintained the highest FVC (70.4 ± 5.4%) compared to FS (62.4 ± 7.1%) and CS (61.4 ± 10.8%), with highly significant differences (H=67.44, p<0.001). Similar patterns were observed for FEV1: at one year, NS had a mean FEV1 of 71.5 ± 12.9%, compared with 51.5 ± 10.7% in FS and 53.0 ± 17.7% in CS (H=64.74, p<0.001). Post-hoc tests confirmed that NS significantly outperformed both CS and FS (p<0.001), while CS and FS did not differ significantly at most time points. The FEV1/FVC ratio followed the same trend: after one year, NS averaged 75.4 ± 5.4% compared to 69.4 ± 7.1% in FS and 69.4 ± 10.8% in CS, with significant between-group differences (H=63.27, p<0.001) (Table 2).

Within-group Friedman tests revealed significant longitudinal improvements in FVC among NS (χ²=13.03, p=0.0015) and CS (χ²=43.95, p<0.001), while FS also improved modestly (χ²=10.84, p=0.004). (Table 3) These data reinforce earlier reports that active smoking accelerates lung function decline and reduces reversibility. (Figure 1) shows the correlation between FVC (% predicted) and FEV1 (% predicted) at one year, with points colored by smoking group (never smokers = green, former smokers = blue, current smokers = red). The regression line demonstrates a strong positive association between FVC and FEV1 across all patients, with current smokers clustering at lower values. (Figure 2) shows violin plots of FVC, FEV1, and FEV1/FVC across smoking groups. Never smokers display higher median values with narrower variability, current smokers cluster at lower lung function, and former smokers occupy an intermediate distribution.

Asthma Control (ACQ-5)

At baseline, ACQ scores did not differ significantly among groups (NS=1.1 ± 0.42; FS=1.49±0.35; CS=1.4±0.44; H=0.39, p=0.82). However, divergence became evident by three months (NS=0.8±0.35; FS=1.12±0.36; CS=1.57±0.32; H=53.08, p<0.001), with NS reporting significantly better control than both FS and CS (p<0.01). At one year, ACQ scores further highlighted the disparity: NS averaged 0.59±0.28, compared with 1.02±0.43 in FS and 1.84±0.3 in CS (H=63.24, p<0.001). (Table 4) Friedman tests indicated that all three groups improved over time (NS: χ²=142.78, p<0.001; CS: χ²=16.76, p<0.001), though NS achieved the most pronounced and clinically meaningful improvements. These results mirror prior studies demonstrating reduced steroid responsiveness and persistent inflammation in asthmatic smokers, even under standard therapy.

Exacerbations

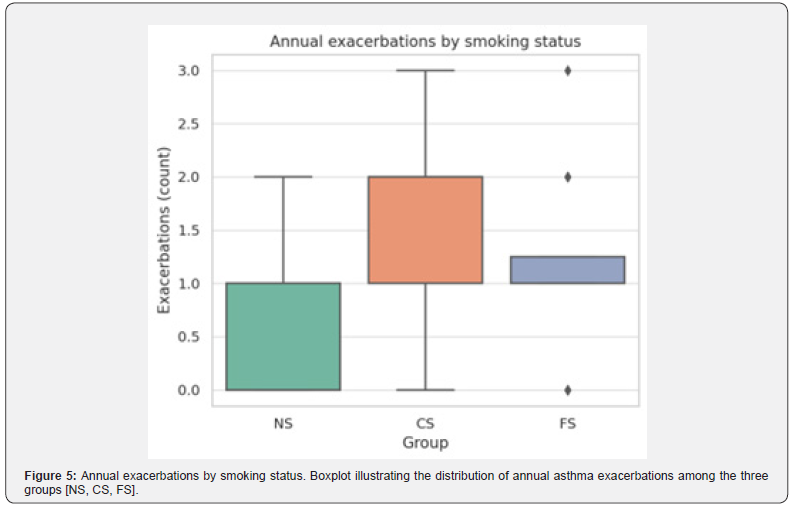

The burden of exacerbations was significantly higher among smokers. CS experienced an average of 2.1±0.42 exacerbations per year, compared to 1.6±0.44 in FS and only 0.8±0.32 in NS. Between-group differences were highly significant (Kruskal-Wallis H=59.65, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that both FS and CS had significantly more exacerbations than NS (Holm-adjusted p<0.001), while FS and CS did not differ significantly. (Table 3) These findings are in line with published evidence that smoking asthmatics suffer more frequent severe exacerbations, hospital admissions, and corticosteroid requirements. (Figure 3) shows the comparison of group mean values for FVC, FEV1, FEV1/ FVC ratio, ACQ score, and annual exacerbations. Never smokers show the most favorable profile, with higher lung function and better asthma control, while current smokers display the poorest outcomes. Former smokers occupy an intermediate position, indicating partial recovery following cessation. (Figure 4) shows the frequency distribution of reported exacerbations in the past year, stratified by smoking status.

Current smokers have the highest concentration of patients experiencing two or more exacerbations, while never smokers are skewed toward fewer events. (Figure 5) shows the Boxplot illustrating the distribution of annual asthma exacerbations in never smokers (NS), current smokers (CS), and former smokers (FS). Current smokers show the highest median and widest variability, while never smokers report the lowest frequency of exacerbations. (Figure 6) mean outcomes at one year, represented by heatmap of mean values for lung function (FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC), ACQ scores, and exacerbations across groups at one year. Never smokers consistently demonstrate the most favorable outcomes, while current smokers show the poorest results, with former smokers in between.

Discussion

Tobacco smoking is one such major modifiable risk factor, that decides the course of the disease and has been linked to worse asthma-specific quality of life, more severe symptoms, higher health care utilization and costs (attributed to unplanned hospital visits and frequent inpatient admissions), higher frequency of exacerbations, faster decline in lung function, decreased response to inhaled corticosteroids, and a higher risk of morbidity and mortality [7]. There is a paucity of published data from India that supports an epidemiological conclusion linking tobacco smoking and worse asthma outcomes. As an aid towards the implementation of more effective smoking control strategies and, ultimately, better outcomes, the goal of the current study is to evaluate the impact of active smoking on asthma patients compared to never-smokers and former-smokers’ clinical outcomes like asthma control and exacerbation risk. In this study about 25.0% of current smokers, 25.0% of past smokers, and 5.3% of never smokers had grade 3 dyspnoea at baseline. The distinction between the degree of dyspnoea and smoking status was statistically significant. In a study by Tiotiu et al. [8], 30% of current smokers had severe dyspnoea as compared to non-smokers & former smokers. There were about 26.7% of current smokers at baseline, which had decreased to 16.0% at three months and 12.0% at 1 year. In a year, there was a 14.7% decrease in smoking.

Among lung function parameters, never smokers had a considerably higher FEV1/FVC ratio, as compared with former smokers and current smokers. And this difference was found to be statistically significant also. In a study by Cerveri et al, the FEV1/ FVC percentage was 78.4 in never smokers, 78.9 in ex-smokers, 78 in quitters and 78.0 in quitters [9]. In a study by Tiotiu et al, the % of FEV1/ FVC ratio was 73 in nonsmokers, 68 in former smokers and 66 in current smokers. In addition, mean FEV1 values at the end of one year were higher in never-smokers as compared to former and current smokers (53.0±17.65 CS vs 51.5±10.7 FS vs 71.5±12.87 NS the difference being statistically significant. In a study by Jang et al, the mean FEV1 % predicted was 84.3 in never smokers, 66.4 in current smokers and 74.1 in ex-smokers [10]. Previous studies showed that smoking has a negative impact on asthma control even though the criteria used to define the control was not always the same [11].

By using the ACQ score to define the asthma-control level in the present study, the ACQ scores were higher for current and former smokers as compared to never smokers at baseline, 3 months and at 1 year of the study and this difference was statistically significant. Thus, current and former smokers had more uncontrolled asthma as compared to never smokers. The mean score at 1 year in CS was significantly higher than that in NS and FS (1.84 vs. 1.02 vs 0.59), indicating poorly controlled asthma in people who continue to smoke (ACQ score > 1.5) [12], in line with other published data. Several studies assessed the effect of active smoking on exacerbation, and showed that adults with asthma who were CS had a higher risk of exacerbation than those who had never smoked [13]. In our study mean number of asthma exacerbation per year in CS was twice as high in this group versus patients who never smoked or ex-smokers and this difference was found to be statistically significant. 55% of current smokers, 56.2% of former smokers and 5.3% of never smokers had at least 2 exacerbations during the study period.

In a study by Tiotiu et al. the number of exacerbations were ≥ 2 in 11% of the nonsmokers, 16% of the former smokers and 48% of the current smokers [14]. These results suggest that smoking cessation could decrease the risk of asthma exacerbations and the need for systemic corticosteroids. Other published data showed that asthmatic patients who are active smokers have an increased number of life-threatening asthma attacks, higher mortality, more frequent episodes of work disability, unscheduled doctor visits, and hospital admissions, suggesting a greater severity of their exacerbations compared to non-smokers [15]. Taken together, these findings confirm a strong association between active smoking status and poor asthma control, as reported in population-based surveys from UK and USA [16]. A previous study also found a significant dose-dependent relationship between pack-years and uncontrolled asthma.

One possible explanation for the poor asthma control in patients who smoke could be that they are less sensitive to the therapeutic effects of inhaled corticosteroids, the most important controller treatment of asthma [17]. These findings must encourage physicians to offer smoking-cessation advice to all asthma patients who smoke, as also recommended by current guidelines. Collectively, these results confirm that smoking asthmatics represent a distinct clinical phenotype characterized by impaired lung function, poor asthma control, and higher exacerbation risk. The intermediate outcomes observed in FS highlight the substantial benefits of smoking cessation, though residual damage is evident. This reinforces the urgent need for integrating structured smoking cessation programs into asthma care. Physicians should emphasize to patients that while cessation improves outcomes, the greatest protection is achieved by never initiating smoking.

Conclusion

Cigarette smoking is associated with worse asthma outcomes for a range of clinical and functional respiratory variables compared to never-smoking. The effect is more important for the asthmatic patients that are current-smokers than in those who decided to quit cigarette smoking. These findings must encourage physicians and asthmatic patients to adopt a no-smoking strategy in order to improve the long-term asthma outcomes in this population. Statistical analysis robustly supports the conclusion that cigarette smoking is associated with significantly worse asthma outcomes across multiple domains, while smoking cessation leads to partial but meaningful recovery. These findings underscore the clinical importance of prioritizing smoking cessation strategies in asthma management to mitigate morbidity and improve quality of life. The strengths of this study are the inclusion of three groups of asthmatic patients with different tobacco-smoking histories and the study of the effects of cigarette smoking on the most important parameters of asthma outcomes: disease control, lung function, and exacerbation rate..

Limitations and Future Directions

This single-center study is limited by the relatively small sample of FS and reliance on subjective measures such as ACQ scores, which may introduce response bias. Additionally, post-cessation ACQ change could not be analyzed due to missing data, precluding quantification of symptom improvement among the 14 patients who quit. Future multicenter longitudinal studies with biomarker assessments (e.g., eosinophilic inflammation, FeNO levels) are warranted to explore mechanisms and recovery trajectories in greater detail.

Acknowledgments

All team members especially Dr Varsha for data collection and preparing master chart, Dr Neethu for logistic support, Dr Madhu for supervision and Dr Imad for statistics and figures. Special thanks to the Department of psychiatry for their advice on tobacco smoking.

References

- GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators (2020) Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med 8(6): 585-596.

- Grippi MA (2015) Fishman’s pulmonary diseases and disorders. Fifth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education Pp: 673-713.

- Polosa R, Thomson NC (2013) Smoking and asthma: Dangerous liaisons. Eur Respir J 41(3): 716-726.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC (2015) Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. Ninth edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders Pp: 679-682.

- Tiotiu A, Ioan I, Wirth N, Romero-Fernandez R, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ (2021) The Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Adult Asthma Outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(3): 992.

- Boulet LP, Lemiere C, Archambault F, Carrier G, Descary MC, et al. (2006) Smoking and asthma: Clinical and radiologic features, lung function, and airway inflammation. Chest 129(3): 661-668.

- Samet JM (2013) Tobacco smoking: the leading cause of preventable disease worldwide. Thorac Surg Clin 23(2): 103-112.

- Tiotiu A, Ioan I, Wirth N, Romero-Fernandez R, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ (2021) The Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Adult Asthma Outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(3): 992.

- Cerveri I, Cazzoletti L, Corsico AG, Alessandro M, Rosanna N, et al. (2012) The impact of cigarette smoking on asthma: a population-based international cohort study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 158(2): 175-183.

- Jang AS, Park JS, Lee JH, Sung-Woo P, Do-Jin K, et al. (2009) The impact of smoking on clinical and therapeutic effects in asthmatics. J Korean Med Sci 24(2): 209-214.

- Chandrashekhar DM, Anandkumar, Jayalakshmi MK, Babu P (2020) Impact of duration of smoking on lung function parameters in young adult males. International Journal of Physiology 8(2).

- Thomson NC, Chaudhuri R (2009) Asthma in smokers: challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin Pulm Med 15(1): 39-45.

- Çolak Y, Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG, Lange P (2015) Characteristics and Prognosis of Never-Smokers and Smokers with Asthma in the Copenhagen General Population Study. A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192(2): 172-181.

- Tiotiu A, Novakova PI, Nedeva D, Chong-Neto HJ, Novakova SM, et al. (2020) Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma Outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(17): 6212.

- Siroux V, Pin I, Oryszczyn MP, Le Moual N, Kauffmann F (2000) Relationships of active smoking to asthma and asthma severity in the EGEA study. Epidemiological study on the Genetics and Environment of Asthma. Eur Respir J 15(3): 470-477.

- Laforest L, Van Ganse E, Devouassoux G, Bousquet J, Chretin S, et al. (2006) Influence of patients’ characteristics and disease management on asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 117(6): 1404-1410.

- Shimoda T, Obase Y, Kishikawa R, Iwanaga T (2016) Influence of cigarette smoking on airway inflammation and inhaled corticosteroid treatment in patients with asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 37(4): 50-58.