Summary

Introduction: Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a rare disease of the third trimester that can engage the maternal-fetal prognosis. The clinical picture is polymorphic.

Objective: To describe the clinical and biological characteristics, management and maternal-fetal fate of patients with AFLP.

Methodology: This is a retrospective, monocentric, descriptive and analytical study over the period from January 1st, 2020 to December 31th, 2024. We included all patients admitted for AFLP after exclusion from differential diagnoses. Swansea criteria were used for the diagnosis of AFLP.

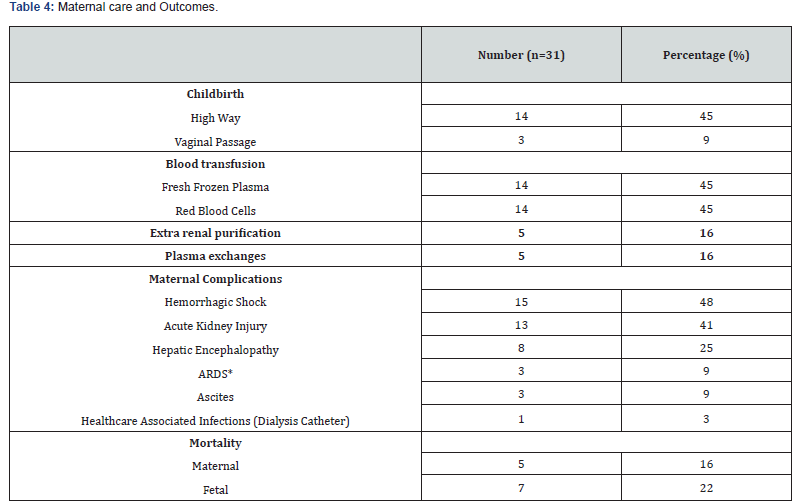

Results: Thirty-one patients were included with a frequency was 1%. The average age was 28 years [18; 41]. The patients were multigravida and multiparous in 64%. The pregnancies were mono-fetal in majority 58%. The average pregnancy term was 34 WA [27; 39]. The clinical characteristics were icterus 87%, nausea-vomiting 67%, Epigastralgia 67%, asthenia 35%, polyuria in 35% and encephalopathy 3%. High blood pressure was found in 16%. The biological abnormalities were hypoglycemia in 54%, anemia in 51%, thrombocytopenia in 32%, leukocytosis in 77%, low PTT in 71%, uremia in 22%, high creatinine level in 45%, hepatic cytolysis in 96% (AST) and 83% (ALT), hyper-bilirubinemia in 80%. Ascites was present in 16% and a hyper-echogenic liver in 13%. A termination of pregnancy was performed in 54% by cesarean section 45%, under spinal Anaesthesia in 85%. Extra renal cleansing was performed in 16%. Plasma exchanges were performed in 16%. The average duration of stay was 6 days [2; 13]. The main maternal complications were hemorrhagic shock in 48%, acute kidney injury in 42%, hepatic encephalopathy in 25%, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in 9%, ascites in 9%. The evolution was burdened with a maternal mortality of 16% secondary to refractory hemorrhagic shock with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome. Fetal mortality was 22%. Risk factors associated with maternal mortality were gestational age, asthenia, hepatic encephalopathy and hemorrhagic shock.

Conclusion: AFLP remains rare but serious. Early diagnosis, correction of haemostasis disorders and rapid termination of pregnancy are key to reducing maternal-fetal morbidity and mortality. This work provides a description of AFLP and its outcomes in the north African context.

Keywords:Acute Fatty Liver Disease; Pregnancy; Swansea Criteria; Coagulopathy; Maternal-Fetal Prognosis

Abbreviations:WFSA: World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists; AFLP: Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; AKI: Acute Kidney Injury; LCHAD: Long Chain Hydroxyacyl-Coa Dehydrogenase; FFP: Fresh Frozen Plasma; ROTEM: Rotational Thromboelastometry; MODS: Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome

Introduction

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a rare third trimester complication. It is responsible for acute liver failure, a hemostasis disorder and acute kidney injury (AKI). It is a medical and obstetric

emergency involving maternal and fetal prognosis. Prospective and retrospective studies suggest an incidence ranging from 1/7000 to 1/20,000 pregnancies [1]. This pathology is associated with a

defect in mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids related to a

deficiency of long chain hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD)

[2]. This results in an accumulation of fatty acids (microvesicular

steatosis) and their metabolites in the maternal circulation. The

clinical picture is polymorphic. Ch’ing et al. had published a study

in which they proposed diagnostic criteria, known as Swansea

criteria, for the diagnosis of AFLP [3]. According to these criteria,

the presence of at least 6 of these characteristics in the absence

of other etiologies suggests AFLP. The Swansea criteria in this

study showed a positive and negative predictive value of 85% and

100%, respectively [4]. The clinical symptoms lack specificity and

an anatomo-pathological examination cannot be performed in

most patients; therefore, the most important criteria are based on

clinical and biological examination results [5,6]. These specificity

and sensitivity defects constitute an additional diagnostic difficulty

in our context. Few North African studies have documented AFLP,

necessitating a local description of clinical profiles and outcomes.

The objectives of our work were:

a) Describe the epidemiological, clinical and paraclinical

characteristics of AFLP.

b) Describe the therapeutic modalities.

c) Identify the maternal-fetal prognostic factors.

Patients and Method

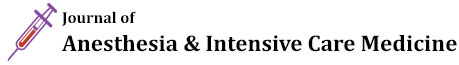

This is a retrospective, descriptive and analytical study over the period of 5 years (January 1st, 2020 to December 31th, 2024) in the obstetric anesthesia-resuscitation department of the university hospital of Marrakech. We included all patients admitted in peripartum in whom the diagnosis of AFLP was suspected or retained on clinical and paraclinical (Swansea) criteria after exclusion from differential diagnoses (HELLP, viral hepatitis, drug-induced hepatitis). We have excluded the incomplete and inoperative medical records. A survey sheet has been preestablished. The data collection was based on patient records and hospitalization and death registers. The maternal epidemiological, clinical, paraclinical, therapeutic and evolutionary data were studied, as well as the fetal prognosis. We used the Microsoft Excel 2016 software for the creation of the database. The quantitative variables were expressed as an average and the qualitative variables were expressed in terms of number and percentage (%). The pathological thresholds of the biological variables of the Swansea criteria were used. The definitions of clinical-biological data are summarized in (Table 1). The statistical analysis was carried out using the Pearson Chi2 test or the exact Fisher test from the Epi Info software version 7.2.2.6. The p value allowing to affirm the existence of a statistically significant difference between two percentages of two variables was set at 0.05.

PTT: Prothrombin Time

Results

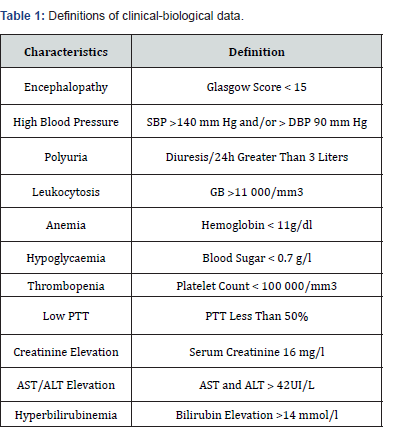

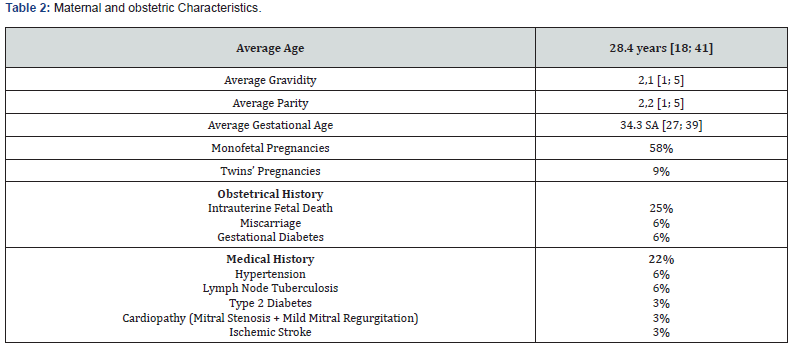

The frequency of AFLP was 1% in our study. The average age was 28 years [18; 41] with a predominance of the age group from 26 to 34 years in 42%. Patients were referred in 61% and came from provincial hospitals 32%, clinics 9% and regional hospitals in 6%. The patients were multigravida and multiparous in 64%. The maternal and obstetric characteristics are described in (Table 1). Among the reasons for admission, there was mucous jaundice in 77%, epigastralgia in 19%, nausea-vomiting in 16%, pre-eclampsia in 12%, right hypochondrium pain in 6%, asthenia in 3%, polyuria in 3% and hemorrhagic syndrome in 3%. Patients were admitted during antepartum in 54% and post-partum in 45%. (Table 2) shows the distribution of patients according to the main clinical and paraclinical characteristics. The therapeutic management consisted of an interruption of pregnancy in 54% by caesarean section 45%. This termination of pregnancy was performed under spinal anesthesia in 85% (Table 3). The administration of diuretics 29% and extra renal cleansing in 16%. The correction of coagulopathy with the transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) 45%, red blood cells 45%, administration of fibrinogen 3% and vitamin K 29%. Plasma exchanges were performed in 16%. In patients who benefited from plasma exchanges, the average of the sessions was 2. Plasma exchanges were performed with FFP and albumin infusions. No complications related to plasma exchange were reported.

PTT: Prothrombin Time

The management of associated preeclampsia by antihypertensives 32 % and magnesium sulfate 19%. N-Acetyl cysteine was administered in 9%. The average duration of stay in intensive care was 6 days [2; 13]. The stay was less than 5 days in more than half of the patients (51.7%). The maternal complications were hemorrhagic shock in 48%, acute kidney injury (AKI) in 42%, hepatic encephalopathy in 25%, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in 9% and ascites in 9%. An infection related to dialysis catheter care was identified as 3%. The evolution was burdened by a maternal mortality of 16%. These maternal deaths were secondary to refractory hemorrhagic shocks with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Fetal mortality was 22%.

Intrauterine fetal death was found in 16% and born deaths in 6%. Acute fetal distress was reported in 6%. (Table 4) summarizes maternal care and outcomes. In the univariate analysis, the risk factors associated with maternal mortality were gestational age (p=0.034), asthenia (p<0.01), hepatic encephalopathy (p=0.02) and hemorrhagic shock (p=0.07). We did not find any maternal risk factors associated with fetal mortality.

ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Discussion

This is a retrospective study over a period of five years. We had collected 31 cases of AFLP with a frequency of 1%. This low frequency confirms the literature on the rarity of this pathology [7]. The retrospective nature of the study could constitute a selection bias and underestimate the incidence of this pathology. Ch’Ng C L et al. had made the same observation [3]. Prospective multicenter studies would allow for better case detection and a larger cohort to be considered. However, this work is of paramount importance for future work in the diagnosis, management and identification of risk factors in the African and North African context in particular. The pathophysiology of AFLP remains poorly understood. Different studies indicate severe mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver and the association of fetal fatty acid oxidation abnormalities with maternal hepatic involvement. This dysfunction could be triggered by several genetic and acquired factors. The deficiency of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coa dehydrogenase (LCHAD) plays a role in some cases of AFLP [1].

In our study, the average maternal age was 28 years. This average maternal age is similar to that reported by other authors in the literature [7-9]. These are young patients in general, however the maternal age was not found in our study as a prognostic factor. We found 64% of multigravida and multiparous patients. Multigravidity is described by Susan McBride et al as a risk factor for the occurrence of AFLP [10]. The average gestational age was 34 WA [27; 39]. AFLP is indeed a third trimester pregnancy pathology. In the literature, other authors found similar results to ours with respective gestational ages of 36 ± 2.76 WA, 35.8 ± 2.3 WA and 31 WA [9-11]. Our analytical study found gestational age as a risk factor for maternal mortality. In more than a third of cases (38%), the patients had a gestational age greater than 35 WA. Gestational age also influences fetal prognosis with risk of prematurity, respiratory distress and neonatal death. Male gender was described in the literature as a risk factor for AFLP occurrence, unfortunately neonatal sex data were not reported in our series.

The Swansea criteria were proposed to diagnose AFLP by Ch’ng in 2002 [3]. According to some authors, these criteria have a good sensitivity, but lack specificity for the diagnosis of SHAG [7,12,13]. The main clinical manifestations found in our study were: mucous jaundice in 87%, nausea-vomiting in 67%, epigastralgia in 67%, asthenia in 35%, polyuria in 35%, arterial hypertension in 16% and encephalopathy in 3%. Our clinical results are consistent with the results of several authors in the literature [7,10,13].

The overlap between AFLP and preeclampsia has been reported in the literature with higher prevalences than ours [4,6,10,14]. Goel et al. applied the Swansea criteria to a group of patients diagnosed with AFLP who then underwent a liver biopsy [4]. The Swansea criteria in this study showed a positive and negative predictive value of 85% and 100%, respectively. This latter study also pointed out that more than half of the patients who met the Swansea criteria for AFLP also met the criteria for HELLP syndrome, partial HELLP syndrome and liver changes secondary to preeclampsia, thus showing the overlap of diseases and difficulties with the diagnostic utility of Swansea criteria [4]. A more recent study by Devarbhavi et al had confirmed this overlap [14]. These investigators reported low accuracy for the diagnosis of AFLP based on the Swansea criteria while pointing out that HELLP and acute viral hepatitis also met many diagnostic criteria [14]. This is what explains the association with preeclampsia found in our study at around 16.1%, making differential diagnosis difficult.

The main biological abnormalities found were: hepatic cytolysis in 96% (AST) and 83% (ALT), hyperbilirubinemia in 80%, leukocytosis in 77%, low PTT in 71%, hypoglycemia in 54%, an increase in serum creatinine in 45% and thrombopenia in 32%. Anemia was found in more than half of the patients, 51%. This anemia would be multifactorial related to coagulopathy on one hand and hemolysis on the other. These results confirm the trend found in the literature [7,13]. These same authors consider that biological anomalies are more specific to AFLP [13]. The biological abnormalities found in our study are consistent with Swansea’s biological criteria. The abdominal ultrasound had found ascites in 16% and a hyper-echogenic liver in 13%. The ultrasound and/or CT scan can be of valuable help in the diagnostic process. However, their normality does not exclude this condition [15]. In a study by Castro et al, the authors attempted to confirm the diagnosis of AFLP based on several imaging modalities, but were only able to do so in 30% of patients, leading them to conclude that there was no benefit from imaging [16-18]. These results were repeated in a study by Nelson et al. who showed an ultrasound confirmation rate of AFLP at 27% [6].

Nevertheless, since imaging is non-invasive, it remains an essential part in eliminating other differential diagnoses. Moreover, the confirmation remains nevertheless histopathological, it seems that the indication of the hepatic biopsy puncture is limited to situations in which the evolution of clinical, biological or radiological parameters makes the diagnosis of AFLP [15] controversial. The presence of coagulopathies limits its realization. In the past, liver biopsy was used for diagnosis, but this is no longer systematic and not necessary for confirmation. The liver biopsy was not performed in our series. The cornerstone of AFLP treatment is fetal delivery, which is the definitive treatment [13]. In addition to the rapid diagnosis of AFLP, supportive care and correction of coagulopathy while making preparation for childbirth are required. The data on the delivery route are divergent and inconclusive. It can be done vaginally or by caesarean section. The main advantage of a vaginal delivery is to avoid a possible worsening of coagulopathy, so that the vaginal delivery must be continued as long as the fetus and mother tolerate labor. However, fetal distress is common due to maternal acidosis due to liver failure [13]. The major advantage of a cesarean delivery is its ability to speed up the delivery of the fetus in case of fetal distress. For this reason, cesarean section is more commonly used. White reports a 55% cesarean section rate similar to our result (45%) [13]. Nevertheless, cesarean section was associated with higher rates of common complications including postpartum hemorrhage, coagulopathy and renal failure [13,19].

This state of affairs could be due to the initial severity of the clinical picture requiring urgent fetal extraction in this field of coagulopathy. The correction of coagulation disorders must be done before fetal extraction and must be guided by the biological results of conventional haemostasis through the infusion of FFP and platelets possibly, fibrinogen. In this context, rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) has become a subject of interest in all cases of postpartum hemorrhage due to its potential management of coagulopathy. It could improve the management of hemorrhagic shock secondary to AFLP, but data are limited in the obstetric population. One case was found that demonstrated the use of ROTEM in a woman with AFLP [18]. The observation is that the main advantage of ROTEM in AFLP and bleeding is management during recovery rather than in the middle of postpartum hemorrhage. The anesthetic technique will depend on the clinical condition and the presence or absence of coagulation abnormalities and/or thrombopenia. In our series, spinal anesthesia was performed in 85%. Plasma exchanges and hemodialysis were performed in 16.1% each. Plasma exchanges are discussed on a case-by-case basis. In our cohort, they concerned the most severe forms. The interpretation of a possible effect on mortality is therefore limited by an indication bias. Plasma exchanges allow to relieve liver damage by temporarily replacing the liver function while allowing time for liver regeneration. Plasma exchanges alone have been shown to improve oxidative stress and soothe liver function recovery, but the benefit of mortality in AFLP patients has been debated. Indeed, the data on the impact of plasma exchanges on maternal mortality in AFLP are divergent [18-20]. Plasma exchange in combination with continuous hemodiafiltration therapy has been shown to improve outcomes, but studies are limited to small cohorts [20].

In our study, the maternal complications were hemorrhagic shock in 48%, acute kidney injury (AKI) in 42%, hepatic encephalopathies in 25% and ARDS in 9%. Hemorrhagic shock and AKI are linked to bleeding/coagulopathy secondary to liver failure. Zhang et al had identified coagulopathy in 54%, AKI in 39% and ascites in 36% [21]. Respiratory distress would be linked on the one hand to pulmonary edema and on the other hand to the inflammatory storm in this context of peri-partum, all aggravated by the physiological changes of pregnancy which would also play a role in the process of AFLP. Maternal and fetal mortality were 16% and 22% respectively. The overall maternal and perinatal mortality rates according to some authors were 15% and 19% respectively [13,19]. These rates are similar to those found in our study. Zhang also reports a 7% lower maternal mortality secondary to multiple organ failure syndrome. He also reports fetal mortality of 16% and intrauterine fetal distress 26% was the most common neonatal complication [21]. This difference would be linked to advances in early detection and management. The literature indicates a decrease in maternal-fetal mortality rates since 1980, nevertheless the rates remain always high. This high mortality in our series could be due on the one hand to reference delays, late diagnosis (advanced gestational age) with deeper coagulopathies and on the other hand, by the context of limited resources. ROTEM is not yet available and FFP are not always available in quantity. Data on the perspectives of AFLP indexed patients are lacking. Given the increased risk of recurrence in patients with LCHAD mutations, fetuses from AFLP -indexed pregnancy should be screened for a fatty acid oxidation disorder.

Conclusion

In our center, acute fatty liver pregnancy remains rare but burdened by a high morbidity and mortality. Early identification, targeted correction of haemostasis disorders and rapid termination of pregnancy are the major levers for improvement. The establishment of a Moroccan national register of acute fatty liver pregnancy and standardized protocols are necessary to reduce adverse outcomes. Prospective multicenter studies are necessary to specify the place of plasma exchanges and optimize anesthesia/analgesia strategies.

References

- Joueidi Y, Peoch K, Le Lous M, Bouzille G, Rousseau C, et al. (2020) Maternal and neonatal outcomes and prognostic factors in acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 252: 198-205.

- Schoeman MN, Batey RG, Wilcken B (1991) Recurrent acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with a fatty-acid oxidation defect in the offspring. Gastroenterology 100(2): 544-548.

- Ch’Ng C L, Morgan M, Hainsworth I, Kingham J GC (2002) Prospective study of liver dysfunction in pregnancy in Southwest Wales. Gut 51(6): 876-880.

- Goel A, Ramakrishna B, Zachariah U, Ramachandran J, Eapen CE, et al. (2011) How accurate are the Swansea criteria to diagnose acute fatty liver of pregnancy in predicting hepatic microvesicular steatosis? Gut 60(1): 138-139.

- Wang S, Li S, Cao Y, Li Y, Meng J, et al. (2017) Noninvasive Swansea criteria are valuable alternatives for diagnosing acute fatty liver of pregnancy in a Chinese population. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 30(24): 2951-2955.

- Nelson DB, Yost NP, Cunningham FG (2013) Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: clinical outcomes and expected duration of recovery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 209(5): 456.e1-456.e7.

- Tan Jianbo, Hou Fei, Xiong Haofeng, Pu Lin, Xiang Pan, et al. (2022) Swansea criteria score in acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Chinese Medical Journal 135(7): 860-862.

- Marwen N, Azouz I, Issaoui N, BL Hadj J (2022) Steatose Hepatique Aigue Gravidique: A Propos De 5 Observations cliniques et revue de la litterature. Revue marocaine de santé publique 9(15).

- Bahloul M, Dammak H, Khlaf-Bouaziz N, Trabelsi K, Khabir A, et al. (2006) Stéatose hépatique aiguë À propos de 22 cas. Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité 34(7-8): 597-606.

- McBride S, Hurd K, Congly S, Vlasschaert M (2025) Liver disease in pregnancy. Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine 20(2): 81-90.

- Chatbi Z, Rhazi I (2023) La Steatose Hepatique Aigue Gravidique: A Propos De 7 Cas Et Revue De La Litterature. IJAR 11(02): 1109-1115.

- Liu Joy, Ghaziani Tara T, Wolf Jacqueline L (2017) Acute Fatty Liver Disease of Pregnancy: Updates in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. American Journal of Gastroenterology 112(6): 838-846.

- White A, Nelson DB, Cunningham FG (2024) Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy. Reprod Med 5(4): 288-301.

- Devarbhavi H, Venkatachala PR, Devamsh GN, Shalimar YS, Aashik M, et al. (2023) Swansea criteria evaluation in acute fatty liver of pregnancy, hemolysis elevated liver enzyme and low platelet syndrome, pre‐eclampsia, and viral acute liver failure in pregnancy. Intl J Gynecology Obst 163(3): 1030-1032.

- Homer L, Hebert T, Nousbaum J, Bacq Y, Collet M, et al. (2009) Comment confirmer le diagnostic de stéatose hépatique aiguë gravidique en urgence? Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité 37(3): 246-251.

- Castro MA, Fassett MJ, Reynolds TB, Shaw KJ, Goodwin T, et al. (1999) Reversible peripartum liver failure: A new perspective on the diagnosis, treatment, and cause of acute fatty liver of pregnancy, based on 28 consecutive cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 181(2): 389-395.

- Crochemore T, De Toledo Piza FM, Silva E, Corrêa TD (2015) Thromboelastometry-guided hemostatic therapy: an efficacious approach to manage bleeding risk in acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Reports 9(1): 202.

- Peng Q, Zhu T, Huang J, Liu Y, Huang J, et al. (2024) Factors and a model to predict three-month mortality in patients with acute fatty liver of pregnancy from two medical centers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24(1): 27.

- Wu Z, Huang P, Gong Y, Wan J, Zou W, et al. (2018) Treating acute fatty liver of pregnancy with artificial liver support therapy. Medicine 97(38): e12473.

- Li L, Huang D, Xu J, Li M, Zhao J, et al. (2023) The assessment in patients with acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) treated with plasma exchange: a cohort study of 298 patients. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23(1): 171.

- Zhang YP, Kong WQ, Zhou SP, Gong YH, Zhou R, et al. (2016) Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy: A Retrospective Analysis of 56 Cases. Chin Med J 129(10): 1208‑12