Polycistic Ovary Syndrome: Diagnosis And Management In Primary Care

Jorge Sánchez Melús1* and Luz Divina Mata Crespo2

1Emergency doctor, Emergency department, Hospital Ernest Lluch, Spainn

2Primary Care Doctor, Centro de Salud La Muela, Spain

Submission: November 10, 2023;Published: November 14, 2023

*Corresponding author: Jorge Sánchez Melús, Emergency doctor, Emergency department, Hospital Ernest Lluch, Spain

How to cite this article: Jorge Sánchez M, Luz Divina Mata C. Polycistic Ovary Syndrome: Diagnosis And Management In Primary Care. J Gynecol Women’s Health 2023: 26(2): 556185. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2023.26.556185

Summary

Polycistic ovary syndrome (POCS) is a highly prevalent endocrine disorder which is not always diagnosed in young women. We must think about it in any adolescent woman with hirsutism or other skin manifestations of hyperandrogenism, obesity or menstrual irregularities. As it is an exclusion diagnosis, we must do a differential diagnosis from other hyperandrogenic disorder. An early diagnosis is important for a woman’s health (reproductive, oncologic and metabolic risk) and, therefore, as doctor we must follow up for a long term. The treatment should always start with correction of metabolic derangements.

Definition

Polycistic ovary syndrome (POCS) is a set of symptoms related to an imbalance of hormones that can affect women of reproductive age. We can define it as the combination of signs and symptoms of androgen excess, ovarían dysfuntion and polycistic ovarían morfology on ultrasound [1]. In Primary Care, we can define it as underrecognized, underdiagnosed and understudied: at least 70% of women with PCOS remain underdiagnosed [2].

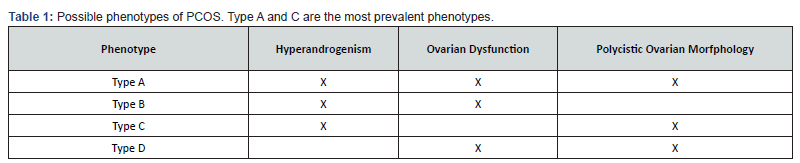

It is important to know how PCOS is defined and categorized. “Polycistic” does not primarily define this syndrome [3]. In the POCS pathophysiology at least three types of interrelated alterations stands out: neuroendocrine dysfunction (hypersecretion of Luteinizing Hormone), metabolic disorer (hyperinsulinemia and insuline resistance) and a dysfunction of steroidogenesis and ovarían folliculogenesis. To make it easier, in Rotterdam (2003) a criteria to be diagnosed was published. We can diagnose it by, at least, two of three diagnostic criteria (Rotterdam criteria [4]):

Hiperadrogenism: high levels of androgens lead to dermatological symptom [5]: hirsutism, acné, balding, alopecia. As Primary care doctors, we have to know that these symptoms can also be caused by puberty rather than PCOS. If it was necessary we could ask for laboratory tests to do a differential diagnose: Total Testosterone (recommended Free Androgen Index [6]: Testosterone/SHBG>4.5, dehydroepiandrosterone (suprarrenal cause of hyperandrogenism), androstenedione (commonly elevated in menopausia), 17-hidroxiprogesterone (21-hidroxilasa déficit), LH/FSH>2 (not used in the last years).

Menstrual disorders: they can vary from amenorrea to oligomenorrea (menstruation delayed to 35 days or more) to menorrraghia. It can cause several problems to women who suffer from POCS: women with PCOS are 15 times more likely to report infertility [7].

Polycystic Ovaries (only available thanks to ultrasound): excessive follicles (25 or more from 2 to 10mm in a transvaginal ultrasound) may be present. Furthermore, increased ovarían volumen (more than 10mL) may be present [8] (Table 1).

Treatment

a) As Primary Care doctors, we must help the patient with non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment. We must be honest with the patients and explain them that there is no cure for PCOS, but symptoms can be managed with lifestyle changes and medication:

b) Obesity is recognised as aggravating PCOS, especially abdominal circumference [9]. In addition, exercise helps to reduce many PCOS symptoms. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week or 75 minutes of high-intensity exercise per week and strength training 2 days per week [10].

c) Avoid inflammatory foods (gluten and high glycemic load: potatoes, bread, sugary desserts…) [11].

d) Low-androgen oral contraceptives (most common used: drospirenone or progestin-only pills): they are considerated first pharmacological step. They will suppress LH secretion and decrease ovarían androgen biosynthesis [12].

e) Metformin: reducing insuline resistance.

f) Lipid-lowering agents for women with lipid abdormalities.

Long-Term Medical Follow-Ups

a) As Primary Care doctors, we must be prepared to follow up regularly these patient (as we said before, this is a chronic disease):

b) Blood sugar test once a year and Hemoglobin A1C test once a year.

c) Vitamin D level test.

d) Thyroid function test.

References

- Trikudanathan S (2015) Polycystic ovarian syndrome. Med Clin North Am 99(1):221-235.

- Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Timothy JK, Knochenhauer ES, et al. (2004) The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(6): 2745-2749.

- Escobar-Morreale HF (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 14(5): 270-284.

- The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM (2004) Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and longterm health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fértil Steril 81: 19-25.

- Keen MA, Shah IH, Sheikh G (2017) Cutaneous Manifestations of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Clinical Study. Indian Dermatol Online J 8(2): 104-110.

- Fox R, Corrigan E, Thomas PA, Hull MG (1991) The diagnosis of polycystic ovaries in women with oligo-amenorrhoea: predictive power of endocrine tests. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 34(2): 127-131.

- Joham AE, Teede HJ, Ranasinha S, Zoungas S, Jacqueline B, et al. (2015) Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: data from a large community-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 24(4): 299-307.

- Clark NM, Podolski AJ, Brooks ED, ChizenDR, Pierson RA, et al. (2014) Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Phenotypes Using Updated Criteria for Polycystic Ovarian Morphology: An Assessment of Over 100 Consecutive Women Self-reporting Features of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reprod Sci 21(8): 1034-1043.

- Patel S (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), an inflammatory, systemic, lifestyle endocrinopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 182: 27-36.

- (2018) US Department of Health and Human Services, 2018. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, In: (2nd Edn).

- Bates GW, Legro RS (2013) Longterm management of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). Mol Cell Endocrinol 373(1-2): 91-97.

- Wang QY, Song Y, Huang W, Xiao L, Qiu-Shi W, et al. (2016) Comparison of Drospirenone- with Cyproterone Acetate-Containing Oral Contraceptives, Combined with Metformin and Lifestyle Modifications in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Metabolic Disorders: A Prospective Randomized Control Trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 129(8): 883-890.